When did the language of job adverts become so arcane? It is a language unto itself – a meta-language that seems to lack referents in what passes for the concrete fabric of reality today. Who can actually point at a stakeholder and say, as Wittgestein once did of a tree, ‘I know that that’s a stakeholder’? But it is a word that persists in its internal and external form. A stakeholder can mean everything from a customer to the CEO, or a school pupil (internal) and their parent (external). These terms have a nasty habit of leaving their parochial domain (the corporate world) and infiltrating all institutions – schools, universities, hospitals, libraries – at least in their job ads.

Workflow is another advertisement leitmotif, its concise vagueness perhaps meant to suggest fluid working methods, a liquid labouring that is as ceaseless as the 19th Century Thames in its outpouring of productivity. Such opaque rhetoric is the language of neo-liberalism – the language of the free market that ‘corporatises’ vocations to better engineer a return on investment. Here is Corporate Realism, Capitalist Realism’s PR firm: a future-oriented, growth-minded, ‘strivers-not-skivers’ tone and lexicon. At work is a brutal anti-poetry, where words become connotation engines, suggesting economic import at every linguistic turn. It is both exhausting and perplexing, since this job-specific language only seems to exist within this strange realm of job applications.

It is a discourse trapped in the symbiotic exchange between advert and applicant. The selection process starts here, with recognition of the rules of the game, the phrases which are to be repeated back at the parental job provider. Only the worthy individual who can pluck these semantic implements from the text and wield them correctly in their application will enter the kingdom of gainful employ. This is your initation into the cult of modern work – the mastery of its esoteric language.

You will be experienced in x. You will implement y. Another noticeable feature is how driven the rhetoric is – as driven as you must be to meet its demands. In keeping with the going-forward-isation of our times, the future is a utopia which you will have helped shaped through continuous improvement. It is a peverse twist on the Heraclitean notion of Panta rhei, where everything flows, nothing stands still: for your new employer, the improving will never be done. At the same time, communication can only ever occur across multiple channels, meaning you must be able to handle audio, video, and written ‘content’. That latter catch-all term is one I have examined already. Elsewhere, the language of business and warfare (‘strategic aims’) permeates even a post for a Special Educational Needs Teaching Assistant. Austerity, meanwhile, is visible in the sprawling duties and responsibilities whereby two or more positions have clearly been sandwiched into one starring ‘role’.

Yet use these words you must. A university workshop on CVs and cover letters instructed me how employers now perform keyword scans, outsourcing their own Human Resources labour to an algorithm – an irony that is too disheartening to be ever so droll. So I beat on, a solitary boat against the workflow, borne back ceaselessly into the Corporate Realist present.

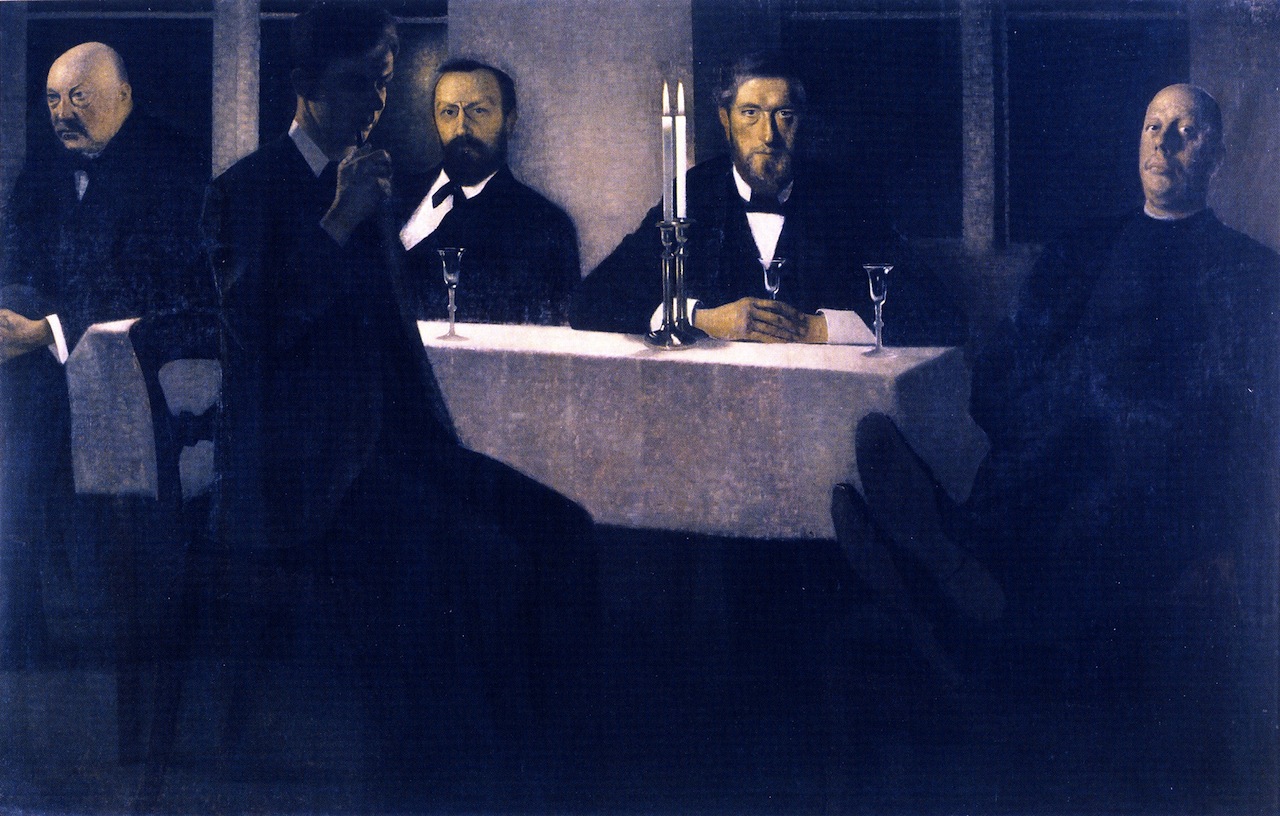

Featured image by Ed Burtynsky of a Chinese factory.